First map of rare mantle earthquakes compiled

Beneath the Surface: How the First Map of Rare Mantle Tremors is Changing Geology

For generations, we have viewed the Earth beneath our feet as a series of distinct, isolated layers. We live on the cold, brittle crust—the only part of the planet we thought was capable of “snapping” to create the earthquakes we feel. Below that lies the mantle, a massive, 1,800-mile-thick expanse of semi-solid rock that geologists long described as “ductile” or “plastic,” implying it was too soft and warm to support the sudden ruptures of a seismic event.

The Mystery of the “Warm” Layer

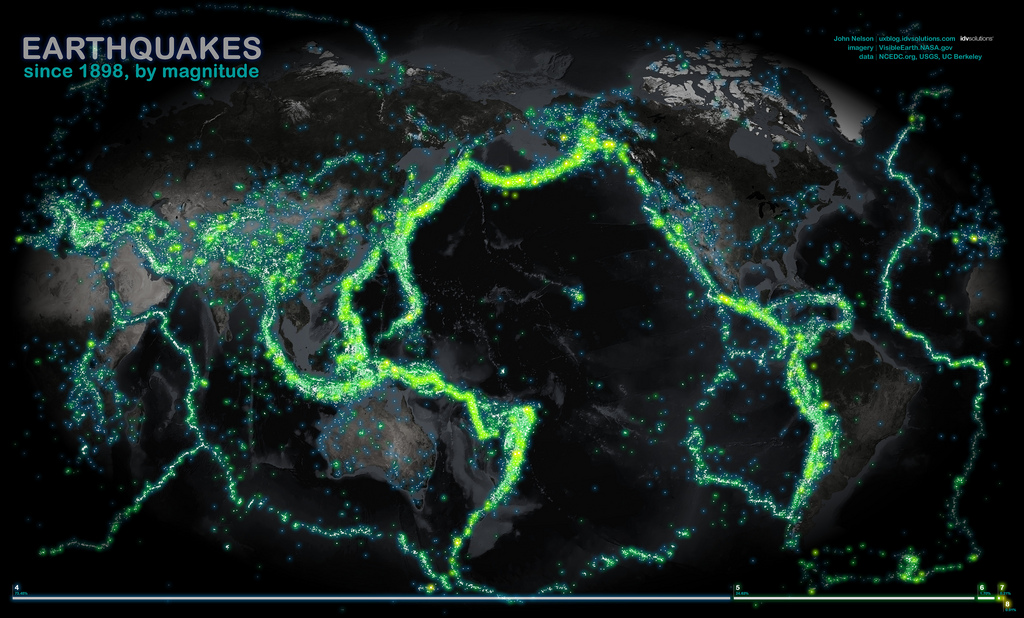

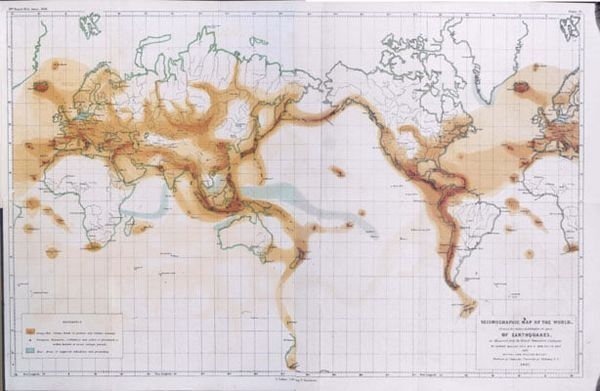

To understand why the First map of rare mantle quakes is such a scientific milestone, we have to look at the physics of the Earth. Most of the earthquakes we experience occur at depths of 10 to 30 kilometers. At these depths, the rock is cool enough to remain brittle. When tectonic plates shift, the rock resists until it eventually breaks, releasing energy as a crustal earthquake.

As you go deeper, the temperature rises. Because of this, the scientific community was skeptical that the mantle could “break.” Yet, the First map of rare mantle tremors proves that in specific regions, the mantle maintains enough rigidity to produce “continental mantle earthquakes.”

A New “Signature” in Seismology

How do you map something that is happening 80 to 100 kilometers underground when the signals are drowned out by shallower noise? This was the primary hurdle for lead author Shiqi (Axel) Wang and geophysics professor Simon Klemperer.

The breakthrough came from a sophisticated method of comparing two types of seismic vibrations:

Sn waves: “Lid” waves that travel specifically along the uppermost layer of the mantle.

Lg waves: High-frequency waves that are trapped and bounce around within the crust.

By examining the ratio of these two signals, the team could distinguish between a quake starting in the crust and one originating in the mantle. This “seismic signature” allowed them to filter through 46,000 seismic events to find the rare gems. The resulting First map of rare mantle quakes identifies 459 distinct events since 1990 that were previously misclassified or overlooked.

Hotspots: The Himalayas and Beyond

The First map of rare mantle activity reveals that these deep quakes aren’t happening everywhere. Instead, they cluster in areas where the Earth’s internal “machinery” is under the most intense pressure.

The most prominent cluster is found beneath the Himalayas. Another surprising hotspot identified on the First map of rare mantle is the Bering Strait. These locations serve as a unique window into the transition zone known as the Mohorovičić boundary (or “the Moho”). Conversely, deep tremors might be the precursors to surface disasters.

By integrating the First map of rare mantle data into existing safety models, seismologists hope to improve earthquake forecasting. If we can understand how the “engine” of the mantle is revving up, we might get better at predicting when the “wheels” (the crust) are about to slip. As Wang noted, the crust and mantle function as a single, interconnected system. Ignoring the mantle when studying earthquakes is like trying to understand a car’s movement without looking at the engine.

The “Conservative” Nature of the Discovery

Interestingly, the scientists believe the First map of rare mantle activity is only the tip of the iceberg. Because monitoring stations are sparse in remote areas like the Tibetan Plateau or the Arctic, many deep quakes likely go unrecorded.

“Until this study, we haven’t had a clear global perspective,” said Wang. The First map of rare mantle tremors is considered “conservative” because it only includes events that were recorded with absolute certainty. As we deploy more sensors and use AI-driven tools like the “Stanford Earthquake Dataset” (STEAD), the map will likely fill in with thousands of more events, revealing a planet that is buzzing with deep-seated energy.

Political and Scientific Echoes

This discovery comes at a time of heightened awareness regarding natural disasters. However, the First map of rare mantle tremors reminds us that “national security” also involves understanding the very ground we stand on.

For leaders in regions like the Himalayas, this data provides a new layer of risk assessment. It confirms that the geological “threat” isn’t just a surface-level issue; it is a deep-rooted process that requires international cooperation in seismic monitoring.

Bridging the Gap: Crust vs. Mantle

For decades, geophysicists lived in a world of “either/or.” Either you studied the brittle crust or the flowing mantle. The First map of rare mantle quakes effectively bridges that gap. It shows that the “Moho” boundary is not a brick wall, but a porous zone of interaction where energy and stress are constantly being traded.